The Historian’s Approach to Understanding Terrorism

Historians' knowledge of primary sources, contextual nuances and contingent events show that they have much to offer scholars and policymakers working on terrorism.

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

Editor’s Note: Too often the United States and its allies find themselves in a counterterrorism policy version of the movie “Groundhog Day,” repeating their past mistakes without end. There are many reasons for these failures, but one is the reluctance of historians to weigh in on contemporary policy debates. Richard English, of Queen’s University, argues that this is a mistake and details the many roles that historians can, and should, play in the broader debates on counterterrorism policy.

Daniel Byman

***

H.R. McMaster’s 2020 book, “Battlegrounds: The Fight to Defend the Free World,” argues very powerfully for the centrality of historical understanding for addressing the world’s greatest challenges. Reflecting on U.S. approaches past and present, McMaster—retired lieutenant general, former national security adviser and himself a historian by training—suggests that “[i]gnorance or misuse of history often led to the neglect of hard-won lessons or the use of simplistic analogies that masked flaws in policy or strategy. Understanding the history of how challenges developed would help us ask the right questions, avoid mistakes of the past, and anticipate how ‘the other’ might respond.” McMaster claims that in dealing with adversaries it is important to appreciate rival interpretations of the past: “in order to overcome strategic narcissism, we must strive to understand our competitors’ view of history as well as our own.”

These are important insights, and never more so than in relation to terrorism—one of the problems McMaster dealt with in his distinguished military career. In responding to terrorism in practice, however, states have often been much less informed by historical insights than would have been life-savingly valuable. In the study of terrorism more broadly, historians’ voices have likewise been quieter than they need to be.

It is true that individual historians have made helpful contributions to the study of particular terrorist groups. But—as pointed out recently in “The Cambridge History of Terrorism,” a new edited volume surveying the field—historical scholarship has been much less prominent in academic journals and on academic bookshelves than work drawn from political science, international relations, economics and psychology. Likewise, most academic centers focusing on terrorism are housed not in history but in other university departments.

Why is this? What has been lost as a result? And what should be done to change it? The answers to these questions are somewhat interlinked. Reflection on what a distinctively historical approach to terrorism offers illustrates why history has been a less salient discipline within approaches to terrorism, and also how it could better inform policy and public debates about the ongoing challenge terrorism poses for the United States and other countries.

The Advantages of the Historian’s Approach

So, what are the distinctive insights potentially brought by historians to an understanding of terrorism? First, historians consider the relationship between change and continuity with an eye to long pasts and, by implication, to long futures. This is a crucial aspect of properly understanding the long-rooted and long-term phenomena involved in the creation of terrorists and the outcomes of terrorist violence. The causes and consequences of 9/11 and the U.S.-led response can be properly appreciated only by analysis more historical than most that was applied at the crucial decision-making moments at the time. Historical scholarship on terrorism, for example, suggests that major terrorist adversaries endure for long periods and that, even after their strength has been weakened, they tend to continue in more limited form. President George W. Bush’s talk of finding, stopping and defeating every terrorist group of global reach was therefore ill-judged. Indeed, it misdirected energy toward the extirpation of a threat that should have been understood instead as eminently containable.

Second, historians stress the complex particularity and uniqueness of each context. This is not to deny that insights drawn from one case might be valuable in others. It is, however, to say that understanding terrorism and how best to respond to it requires deep contextual and historical knowledge. Regrettably, such knowledge has sometimes been lacking. It is telling to ask how many first-rate historians of Iraq, for example, thought plausible what was being promised by politicians in 2003 in relation to the U.S.-led endeavor there.

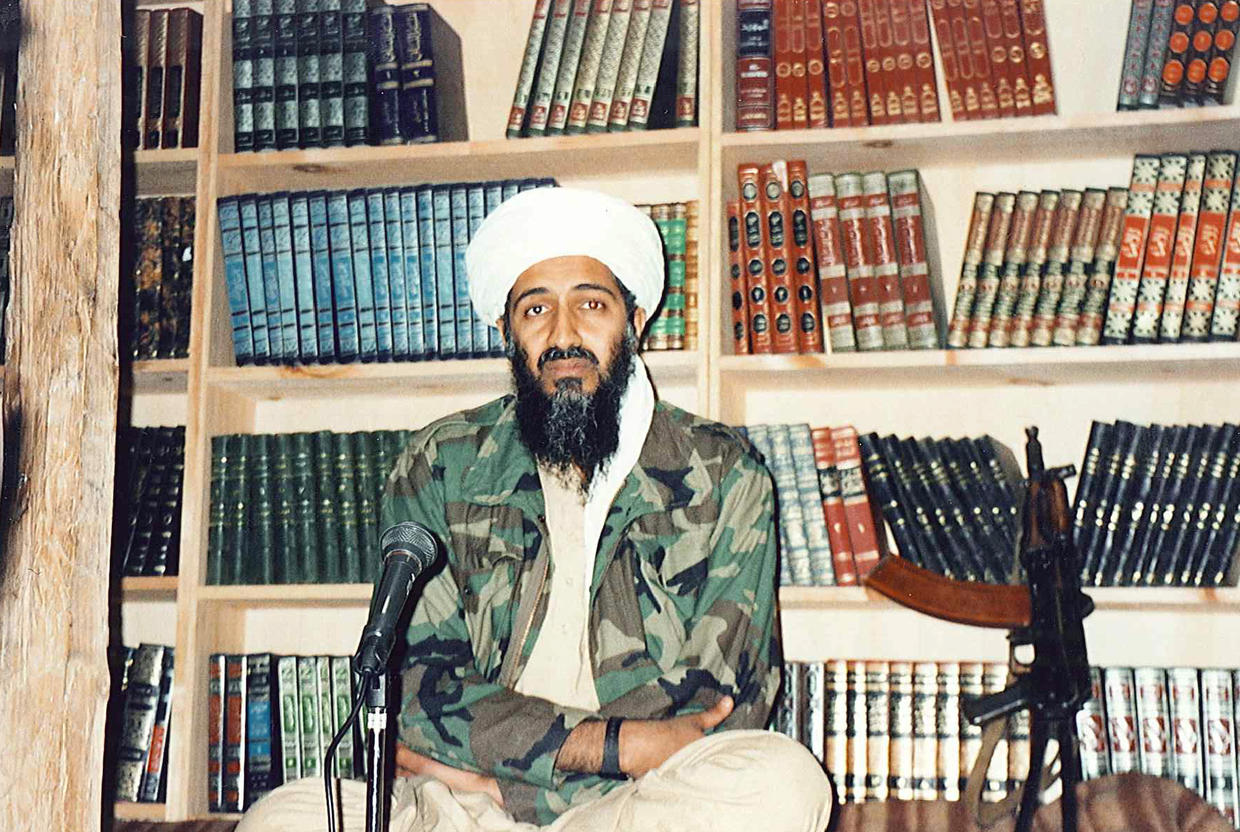

This complex particularity of terrorist context is—my third point—analyzed by historians through engagement with a vast range of mutually interrogatory sources, including many firsthand sources drawn directly from those people under scrutiny. At present, it remains unfortunate that so much research on terrorism is comparatively innocent of what terrorists themselves have said or left behind them. There is a credibility problem as a consequence, not least among the constituencies potentially sympathetic to terrorist groups. This was painfully evident in the complex journey from al-Qaeda, via Iraq, to the emergence of the Islamic State, as political statements by Western leaders stretched plausibility and clashed with contextual realities in major ways. British Prime Minister David Cameron’s 2015 declaration that the Islamic State posed an “existential threat” to the United Kingdom exaggerated the danger of the opponent, but he also underplayed the extent to which British and U.S. actions had helped make the extremist narrative he denounced seem plausible to many people at that time in Iraq and Syria. Historians’ research has made this all too clear, but such insights had far too little effect in key policy-making rooms at crucial moments.

Relatedly, a fourth instinct to which historians frequently tend is skepticism about an overreliance on abstract theorizing, Procrustean and mechanistic theories, or tidy models of explanation. This is not to dispute the value that such theoretical approaches can offer. It is, however, to suggest that those more prescriptive theories are best tested by consideration of the historian’s more jaggedly complex understanding of terrorism and responses to it. Assessments of the efficacy of terrorism, for example, are probably more persuasive if they recognize the many-layered complexity of terrorist aspiration and achievement rather than trying to fit messy human behavior into simplified equations to produce generalizable explanations and predictions.

Finally, historians tend to be skeptical about inevitability in human behavior, preferring instead to stress the role of contingency. The historian’s approach clashes with the teleological assumptions frequently evinced by non-state terrorists and their state opponents alike, it works against seeing the past as a vindicating journey toward a known present or a future hope, and it leads away from overconfidence in the possibility of prediction. This attention to the forking paths the future may take not only is a check against hubris but also can inform better policy. Overconfident declarations—presidential promises to eradicate radical Islamic terrorism from the planet, for example—give gifts to terrorist enemies by establishing goals that are unlikely to be secured.

Historians’ Role in Policy and Public Debate

These five methodological instincts embody something of a distinctive historical approach. Ironically, they both show what is missed when history is downplayed and also why that downplaying has persisted.

Debate about terrorism and counterterrorism policy is usually fueled by obsession with a current crisis or threat. At these moments, historians’ instinct toward long-termism can be seen by some people as a hindrance rather than an advantage. In the wake of 9/11, or the later emergence of the Islamic State, those analysts who focused on the contemporary perhaps seemed more alluring in their answers than those whose approach engaged more with long-term continuities, sources and experiences. But the latter offered deep insights about what would work best, and what would fare less well, in responding to the terrorist challenges that were faced. Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State were clearly different in key ways from each other, and from terrorists past. But there were things to which historical reflection still pointed that would have helped avoid some of the more egregious errors in the “war on terror.” The dangers of an overreliance on military methods, or of conveniently misdiagnosing terrorist origins, or of uncoordinated efforts within and between states, or of less-than-credible counterterrorist political rhetoric, or of the misuse of intelligence—a historically minded, long-termist analysis of terrorism emphasized these vital points and, had they been heeded, many lives could have been saved.

Another reason for historians perhaps being less prominent in policy-facing circles regarding terrorism is that their emphasis on the uniqueness of each context makes their predictions seem rather suspect. If historians also point to contingency in politics, then they might be seen as hostile to exactly those predicted policy outcomes, to those general laws, that governments most seek at times of terrorist crisis.

Many social scientists are more comfortable developing models that facilitate predictions relating to political violence than are historians. Some brilliant work has emerged as a result. Historians tend to be less happy with such patterns of prediction, being less convinced about the past having been governed by general laws.

Accordingly, if a historical approach points toward contingency, complex contextual uniqueness, long-termism and the difficulties of prediction, then it is perhaps unsurprising that historians’ voices have not been the most sought out when states face terrorist onslaught or threat. Arguably, however, historians need to become more engaged in the relevant policy-facing and public debates precisely because these are the advantages that they bring.

Historians’ contribution to debates on terrorism should make them more important to the relevant debates. In responding to terrorism effectively, it is important to possess agility in the face of unanticipated futures and a recognition of the extent to which small numbers of people and their contingent actions can turn the direction of events. These are strengths of historians’ approach.

It is not only through their books and articles, however, or through direct policy engagement, that historians can make a valuable contribution to how society responds to terrorism. As teachers, historians can encourage an informed and reflective approach to the particular, long-term complexities of the human past, in relation to terrorism-generating settings and other scenarios. As graduates, historians can and do affect the world of terrorism and counterterrorism. It is, therefore, perhaps no accident that McMaster is one of the shrewdest of practitioners and policy-influential commentators on terrorism. His best military work in counterterrorism drew explicitly on an awareness of the historical realities and complex inheritances of particular contexts, such as that of Iraq. McMaster exemplifies the advantages of the historian’s approach, whether in research or in practice.