Was the Iraq War a Foreseeable Blunder?

A review of Melvyn P. Leffler, “Confronting Saddam Hussein: George W. Bush and the Invasion of Iraq” (Oxford University Press, 2023).

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

A review of Melvyn P. Leffler, “Confronting Saddam Hussein: George W. Bush and the Invasion of Iraq” (Oxford University Press, 2023)

***

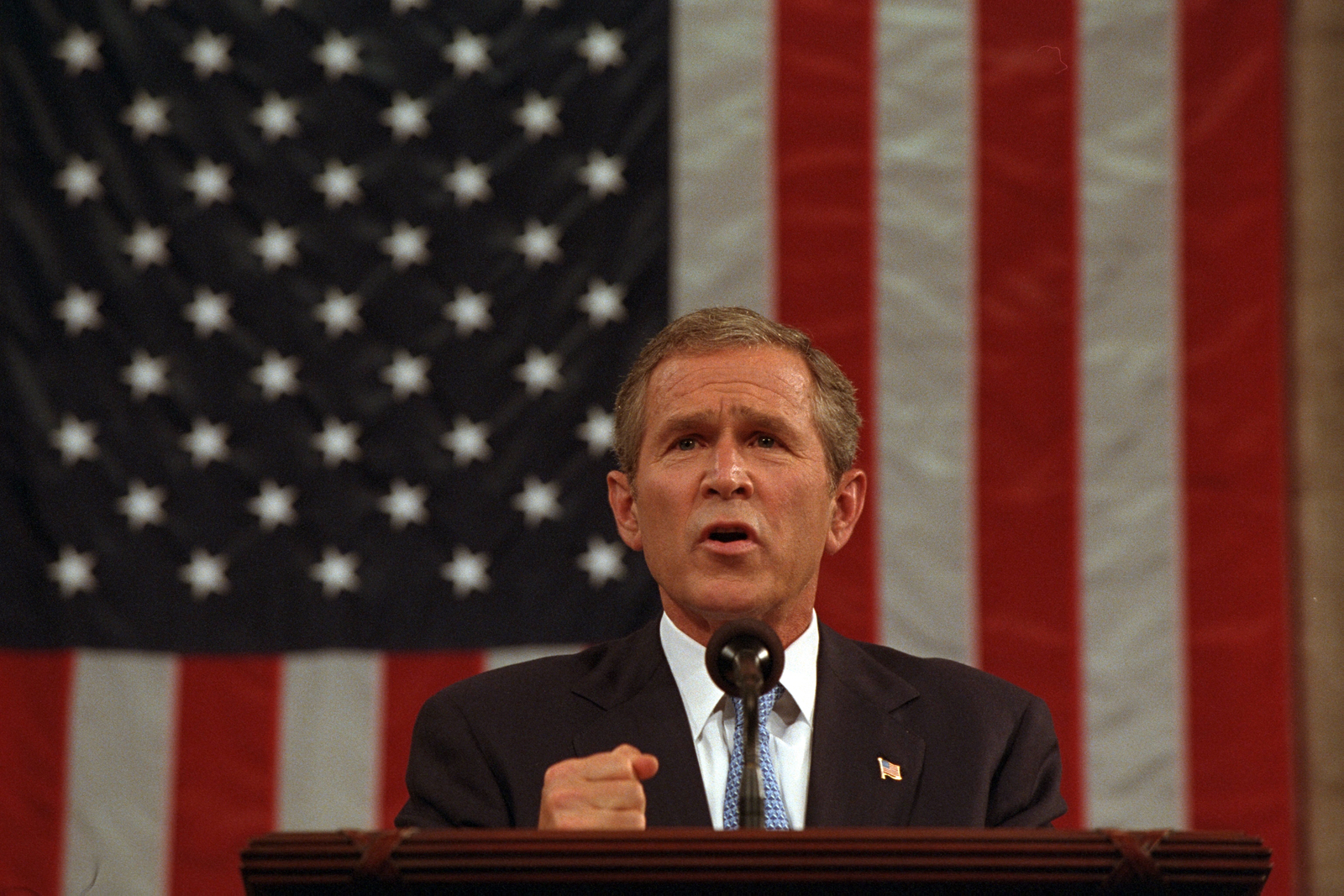

Why did the United States commit the enormous blunder of invading Iraq in 2003? The costs of the war are staggering. Nearly 5,000 American soldiers killed, many thousands more wounded, hundreds of thousands of Iraqis killed and maimed, $2 trillion expended, the empowerment of fundamentalist Iran, intense polarization and the destruction of trust in government at home, and reputational damage across the globe. In view of the catastrophe, prominent Americans who supported the second Gulf War have made a volte face. The historian Max Boot, once a leading advocate of the war, now calls it “all a big mistake.” The commentator Andrew Sullivan, another fervent war hawk, has expressed profuse regrets for being wrong. And then there are the many politicians, like Hillary Clinton, who have apologized for their vote to authorize the employment of American military force.

With hindsight, all is clear: The ending is known. But every historical event must be looked at from two directions. The key question for understanding is always how events appeared at the time to decision-makers struggling with uncertainty. Was there justification for what they did? Or was it obvious, even at the time, that they were on a profoundly mistaken course? There is also a counterfactual imponderable that must be weighed: What kind of ending, including disaster, might have unfolded had they embarked on an alternative path?

In seeking to answer such questions about America’s second Iraq war, we are now blessed with a historical reconstruction of the George W. Bush administration’s choices by the historian Melvyn Leffler. The story he tells in “Confronting Saddam Hussein”—based on extensive documentary research, interviews with everyone who was anyone in the decision-making tree, and years of thinking about the subject—is as complex as it is gripping.

Nothing about the decision to go to war in Iraq can be understood without gauging the impact on the Bush administration of the disaster of Sept. 11, 2001, and the anthrax attack that began shortly thereafter. The former, it became quickly apparent, was the work of al-Qaeda. The latter, the employment of a weapon of mass destruction, was a terrifying mystery, with Iraq’s brutal dictator Saddam Hussein a possible culprit. But whoever was behind the attacks, action to avert a follow-on attack was an urgent necessity. “Everyday since [9/11] has been September 12” is how Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s national security adviser, described the atmosphere in the White House. “We all had the overwhelming sense that we were still one step behind the terrorists and in danger of another successful attack.”

Less than two weeks after 9/11, Bush declared a global war on terror. Leffler notes that, although Afghanistan, the homebase of al-Qaeda and Osama bin Laden, was to be the principal theater, “Iraq remained a burning problem.” No evidence emerged suggesting that Hussein was behind 9/11, but a lot of solid intelligence demonstrated that he was directly involved in sponsoring terror attacks around the Middle East and points further afield. A lot of other intelligence—which turned out to be far less than solid—demonstrated that Hussein possessed chemical and biological weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and was acquiring nuclear weapons as well. On top of that, Hussein was the only world leader who praised the Sept. 11 attacks. Then, three days after the first American died from anthrax, an Iraqi newspaper opined that “[t]he United States must get a taste of its own poison.” The ever-present danger, in the minds of the Bush administration, was that Hussein would provide WMD to a terrorist group. The possibility of a second and far more terrible Sept. 11 loomed large in a White House that had already failed to avert a great disaster.

But even the hawks in the Bush administration, in the fall of 2001, did not regard Iraq as an imminent threat and were not advocating for an all-out war. It is an easily exploded myth, Leffler demonstrates, that the Bush administration decided on attacking Iraq immediately after 9/11 and then lied to the public about the intelligence. It is equally a myth that the U.S. invaded Iraq as part of some neoconservative project to bring democracy to the Middle East. Instead, the Bush administration had a twin focus: to guard against another attack on the homeland and to prevent a nuclear-armed Iraq from dominating the Middle East. Toward those ends it began to pursue two approaches, both in tension with one another. The first was regime change: get rid of Hussein, perhaps by encouraging a coup or forcing him to flee. The second was disarmament: leave Hussein in place but persuade him to surrender his WMD.

Accomplishing either of these goals would require “coercive diplomacy,” the central theme of Leffler’s book:

Bush wanted to intimidate Hussein. He wanted to use the threat of force to remove the Iraqi dictator from power. He also wanted to use the threat of force to resume inspections and gain confidence that Iraq did not possess weapons of mass destruction. He did not really know which of these two goals had priority. They were distinct, yet often conflated. He sometimes wanted Hussein’s removal in order to feel assured there was no threat of WMD falling into the hands of terrorists; at other times, he wanted to use the threat—the demand for inspections—as a ruse to justify military invasion in order to overthrow him. These conflicting, overlapping impulses coursed through Bush’s mind for the next year. He never clearly sorted them out, yet each would become more and more compelling.

As the Bush administration wrestled with how best to confront Hussein, a steady stream of alarming intelligence flowed in. In May 2002, a senior al-Qaeda planner, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, turned up in Baghdad. An intelligence report noted that, in addition to Zarqawi, “other individuals associated with al-Qaida are operating in Baghdad and are in contact with colleagues who, in turn, may be more directly involved in attack planning.” Some 200 al-Qaeda terrorists, possibly under the leadership of Zarqawi, had moved into an ungoverned region in northeastern Iraq, where they were experimenting with biological and chemical warfare. U.S. intelligence, reviewing all the evidence, issued an assessment that Iraq’s reconstituted biological weapons program posed “a credible but elusive threat.”

The pressure for military action grew. The Pentagon prepared a new Iraq war plan, which Bush approved. But as Leffler emphasizes, “war planning did not mean war”; the planning was all part of the pressure campaign. Bush continued to have reservations about going to war and continued to hope that coercive diplomacy would achieve results. The British foreign secretary, Jack Straw, spelled out what he called the Iraq “paradox”: namely, that “diplomacy had a chance of success only if it was combined with the clearest possible prospect that force would be used if diplomacy failed.” Leffler walks readers through the subsequent intense diplomacy, both public and in the halls of the United Nations, where Bush addressed the General Assembly, holding open the possibility that Hussein might remain in power if he acceded “immediately and unconditionally” to disclose and destroy all of his illicit weapons of mass destruction.

Of course, as we now know, Hussein did not have such weapons. But, unfortunately, neither did he come clean about his past record of cheating on their proscription, fueling suspicion about his present WMD capabilities. In Leffler’s analysis,

[Hussein] thought he could outsmart and defy the Americans. He did not think the Bush administration would use force to remove his regime. Believing that Washington had no good reason to invade Iraq—the United States, in his view, already had a position of preponderance in the region and was sure they knew he had no weapons of mass destruction—he calculated that the Americans were playing a game of bluff with him. They wanted to intimidate and force him to flee, but he was confident they would not invade and risk casualties.

Leffler takes readers through the deployment of military power designed to coerce Hussein and, if coercion failed, to destroy his regime. As late as January 2003, as the U.S. was moving forces into position around Iraq, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was still operating in support of Bush’s coercive diplomacy even as he was coming to believe that, thanks to Hussein’s recalcitrance, war was inevitable. Secretary of State Colin Powell was still searching for a diplomatic solution. But Hussein remained defiant. By March, the difficulty was that troops were already in the field. They could not sit in place for months as summer approached and the heat imposed impossible hardship. They could not sit in place making the United States look like a paper tiger. Deployment for the sake of coercion set in motion an almost unstoppable chain of events. The result, on March 20, 2003, was war.

Without question, the Bush administration made grave mistakes both in the run-up to the war and then in its execution. The gaps in the intelligence about Iraq’s WMD are the most glaring instance. Leffler recounts the group-think that had taken hold in Washington and in every Western capital, infecting policymakers and intelligence analysts alike. Hawks and doves both “thought they knew” that Iraq had a chemical and biological warfare capability and was aspiring to build a nuclear capability as well. To be sure, some analysts were later to claim that they were bullied and told their superiors what they wanted to hear, but Leffler, after examining the charge, rejects it, writing:

It is not at all clear that policymakers were seeking incriminating evidence, nor evident that analysts felt political pressure. What preoccupied them—analysts and policymakers, alike—was knowledge that they had previously underestimated Hussein’s penchant to cheat. What they knew from their own lived experience—from recent history—was that Hussein had developed and used weapons of mass destruction. Analysts knew, [former CIA deputy director Michael] Morell explained [in an interview], “that he once had the stuff and actually used it.” They knew that he once “was very very close to getting a nuclear weapon, much closer than we thought.” They knew, said Morell—Bush knew, Cheney knew—that Iraq once “had a weapons program that we completely missed.”

With such a backdrop, no one stopped to pause and ask how firm the intelligence was that pointed to the presence of WMD. If they had paused, they would have been forced to recognize that the intelligence was extraordinarily thin, full of untested suppositions, and bolstered by a confidential source—Curveball—known to be a fraudster. To be fair, intelligence analysts were confronting a conceptual barrier that was extremely difficult to pierce. Convinced that Hussein was hiding WMD to get out from under sanctions, they lacked the imagination to conceive that he was deliberately fostering the false impression that he possessed WMD for the purpose of intimidating both Iran and his own populace. Nonetheless, responsibility for failing to pause—to scrutinize the intelligence, to consider alternative hypotheses about Hussein’s behavior—rests heavily with CIA Director George Tenet and, ultimately, with President Bush.

Perhaps even more egregious than botching the intelligence was scanting the day-after questions: Who would rule Iraq once the Iraqi tyrant was gone, and how would they rule it? William Burns, assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern Affairs (and now CIA director), wrote a prescient memo entitled “Iraq: The Perfect Storm” that laid out possible scenarios of what could go wrong before, during, and after an American invasion. In Leffler’s summary (quoting from the memo),

“[I]mmediately after liberation a powerful dynamic will begin mixing U.S. military, media, new Iraqi authorities, paroxysm of revenge, recriminations and angling for power by key constituencies.” Confronted with “inchoate and escalating disorder in the provinces,” administration officials would face “an agonizing decision: step up more direct security role, or devolve power to local leaders.” This meant that “we need to think now about a very big and expensive commitment. This is a five- or ten-year job, not a fast in and out.”

But as Leffler notes, Burns’s warning was hardly a plea against action: Indeed, “it began with an acknowledgment that war and regime change—if done right—‘could be a tremendous boon to the future of the region, and to U.S. national security interests.’”

In any event, Pentagon and State Department preparation for a post-Hussein Iraq was not set up for a five- or 10- or even one-year job. Inside the bureaucracies, there was endless mastication of the key issues—should power be handed over to Iraqis? If so, which ones? How many troops should be left in place to maintain order? What should be done with the Iraqi army and the ruling Baath party?—but no resolution. Such questions were given far less attention than the mechanics of winning the opening battle. Once again, in fairness to the Bush administration, it must be noted that postwar planning was constricted due to the fear that it would convey the erroneous impression that a decision to go to war had already been made. In the end, following a lightning victory in Baghdad, the U.S. military was grossly unprepared.

Bush bears ultimate responsibility for inattention to postwar planning, but Rumsfeld set the tone. As he was later to write: “I did not think that resolving other countries’ internal political disputes, paving roads, erecting power lines, policing streets, building stock markets, and organizing democratic governmental bodies were missions for our men and women in uniform.” The immediate upshot was widespread looting and destruction, which then devolved into a civil war, with American soldiers, now occupiers, as targets. “Mission Accomplished” was the banner greeting Bush on the deck of the carrier USS Lincoln immediately after Hussein was deposed. Hardly. No weapons of mass destruction were found. Years of chaos and bloodletting commenced.

Was this perfect storm foreseeable at the outset? Opponents of the war, pointing to the results, claim vindication in spades. But as Francis Fukuyama, initially a supporter of the war before changing his mind early on, has observed, “[C]ritics who assert that they knew with certainty before the war that it would be a disaster are, for the most part, speaking with a retrospective wisdom to which they are not entitled.” Likewise, apologies for having supported the war rely largely on retrospective wisdom, undermining their worth. The decision to go to war, as demonstrated by Leffler’s exhaustively researched and exquisitely judicious account, was not an obvious blunder—though well hidden beneath the surface was dereliction of responsibility on the part of the nation’s leaders. To the decision- makers in the Bush administration, to a bipartisan majority in Congress, and to much of the public at large, going to war seemed like an eminently reasonable course of action to protect the United States from a gathering threat. It is only the blinding clarity of hindsight that leaves us unable to see that haunting reality.